50 Years of Women at the Naval Academy | About the Painting

50 Years of Women at the Naval Academy

About the Painting

Note: A special thank you to the Waypoints Podcast and Sisterhood of Mother B for sharing the stories of women graduates. This work has been imperative to my research and the stories have impacted me more than you know. Sisterhood of Mother B Podcast: Michele (Cruz) Phillips '98, Shannon Martin McClain '98, Jeannette Gaudry Haynie '98, Kate McCreery Glynn '98, Jennifer Marino Parsons '98, Carrie Howe '98, Beth Ann (Thomas) Vann '98

Why This Moment Matters

I’ll admit, it has not been until recently that I truly began to embrace this milestone as one to be celebrated. I, like many women who graduated from a service academy, survived by downplaying my femininity, despite finding comfort in the things that made me feel like myself. The relationship between femininity and the military is complicated.

While still so much of the experience is universal to any midshipman, you cannot hide what makes you different. The institution's relationship to those differences becomes a part of your story.

It was not until I really began to listen to the stories of fellow female graduates on the Sisterhood of Mother B podcast that I truly understood how important it was to celebrate this occasion. Tragically, the women of this sisterhood began their journeys with hostility towards their sense of community, and I believe we still feel the effects of that today. There remains a lot of trauma that needs healing. For this sisterhood especially, that connection isn't a luxury. It's what we were denied, and what we're building now.

I want the next fifty years of women to be deeply connected, supported in their service, and free to bring their whole selves to it.

That’s me! April, 2011

50 years, 50 class rings, one painting

How is it possible to convey a wildly complex experience across fifty years of even more diverse women in a single painting? There are so many beautiful perspectives on what it means to be feminine, and what the experience has meant to women.

This question haunted me the majority of 2025, until one day it occurred to me that perhaps a single painting could not possibly do every story justice. It’s the wrong medium. I think those need to be interviews, conversations, actual words.

But alas, I am a painter. And what if, instead, I just painted a glimpse of a moment intimate enough to feel recognizable? What if I used objects in a still life?

This painting aims to acknowledge the spectrum of the female experience over the last fifty years through objects. Objects have stories. They can be taken at face value, they relate to universal themes, and they also acknowledge highly specific details from stories of grads. By recognizing the complexities of these memories, we can cherish the great ones and reclaim the ones we buried.

There are in fact 50 rings, to commemorate 50 years of the sisterhood

Setting up the still life in my garage studio.

The Gaze and The Still Life

There’s a term used in art and visual theory called “the gaze.” It’s basically about who’s looking, who’s being looked at, and who holds the power in that exchange. In traditional Western art analysis, the viewer is often put in the dominant position, while the subject of the art (often a woman), is presented as something to be seen, admired, or even consumed.

In this painting, that structure shifts. The artist and the viewer are the “woman,” and in this case, service academy graduates. The subject of the painting isn’t a body. It’s objects. The power moves from being seen to seeing.

This still life is for the women, for the ones who remember what they saw.

My memories of the Naval Academy are of my perspective. When I think of the moments, I think of a pile on my desk, the bookshelf above my rack. I don’t picture a third person portrait of me as a midshipman. I imagine what I saw. My gaze. Our gazes. That is where the agency lives.

The still life is a genre that has often been ranked “minor” to others in art history, not unlike the female perspective. This painting uses that so-called minor genre to elevate a perspective that has too often been treated as minor.

The Universal: What We Share

Many of the objects depicted can also be detached from the female experience. I know I’m not the only one: So many times, I just wanted to be a midshipman.

Not a “girl” midshipman.

What I love about USNA is the universality of the process. Grads of different decades, race, and gender can connect over the shared experiences. That truth offers space for empathy over what is different in a profound way. I daydream about two people with wildly different backgrounds standing in front of a painting that conjures a memory of the same moment, and then discovering they remember it differently. They leave knowing something about each other they didn’t before.

Let’s get into the painting itself:

The Concept in Color

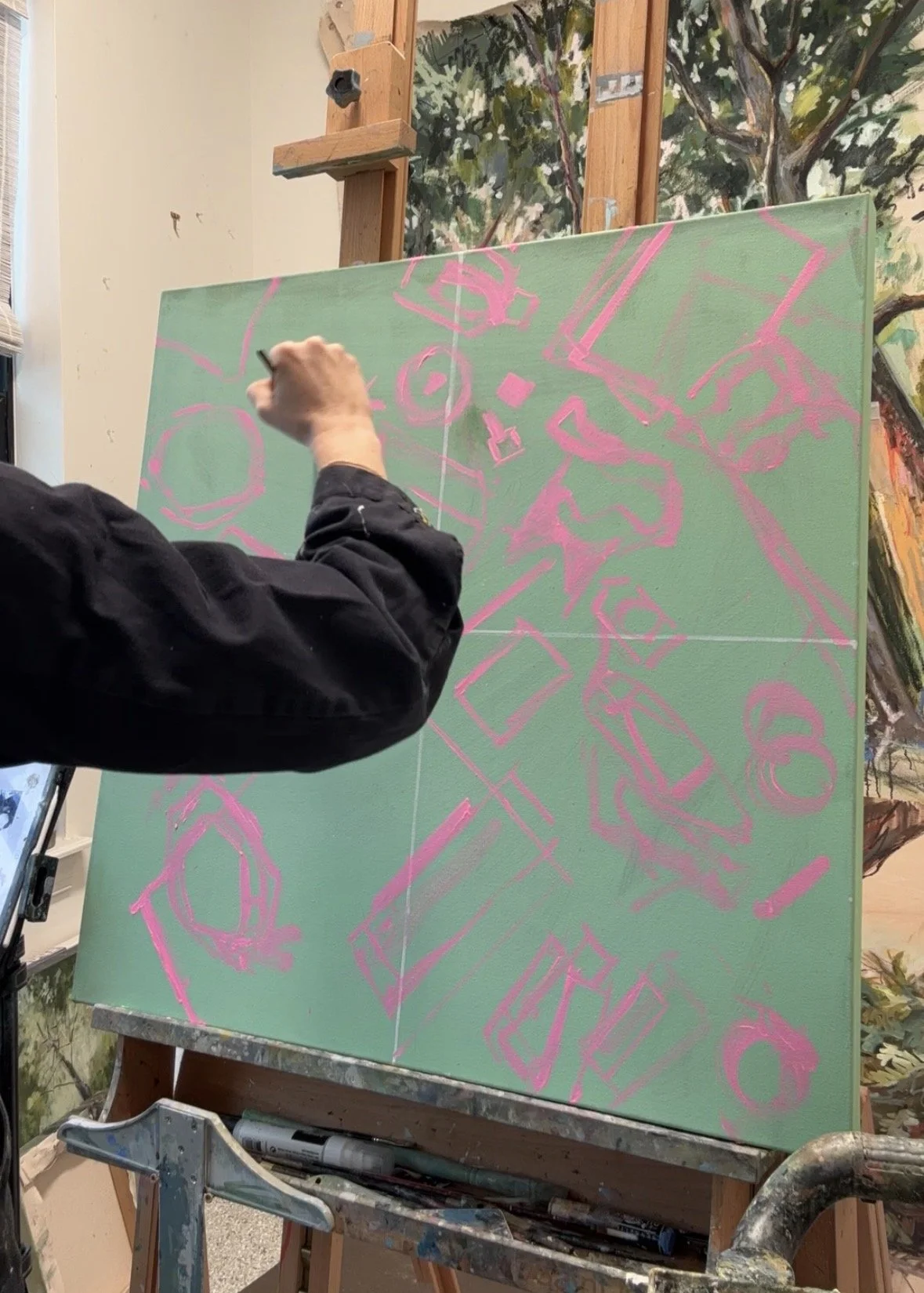

1.The Patina Green underpainting

I chose to cover the canvas with a soft green inspired by the patina color of the copper chapel dome after it ages. This is not only an iconic landmark, it also represents time. It takes time to process the experience. It takes time to trust again after trauma. It takes time to discover the parts that should be savored.

Time changes our relationship to the experience.

While most of this was eventually covered up, it still pokes through in areas and shows on the edge. It’s the foundation for the painting.

2. The hot pink drawing

In one interview, RADM(ret) Peg Klein ‘81 arrived with pink hair in honor of two of her “sisters” who recently succumbed to breast cancer. She explained: “I now wear pink. I need to kick butt because they didn’t have time to.”

I used a strong pink to lay in the initial drawing, eventually painting on top. In modern culture, pink is superficially associated with the feminine. It’s fun. A lot of women’s relationship to “girly” things is heavily informed by their experience at USNA, and often shifts in the time after. The pink in the painting is that reclamation.

Again, most of this is covered up, but it’s foundationally a part of the dialogue and allows the girlhood they carried, and often hid, to inform the experience.

3. The Strong Shadows

The choice to use strong lights and shadows is both an aesthetic and conceptual decision. I love the way it looks, but I also love the way it supports the conversation many women expressed about the duality of their experience.

Male shipmates were friends in private, but kept their distance in public.

A tampon box is taboo and vulnerable, but also useful in hiding contraband.

A boxing mask protects from harm, but also conceals identity.

Female-specific uniform items such as the bucket cover, heels, and neck tab can stand out in the crowd and also result in the person feeling completely invisible.

The Sisterhood

Especially during the early years, it was frowned upon for women to congregate, especially in public. This taboo is one of the most damaging to the individual members of this community, and out of self-preservation instincts, we took part in perpetuating it.

Despite this, female companionship was imperative to make it through the experience, and we have come to realize we do not need permission for it. Now we have that strong connection with each other. The sentiment I heard again and again from the earliest grads was that we needed each other then, and we still do now.

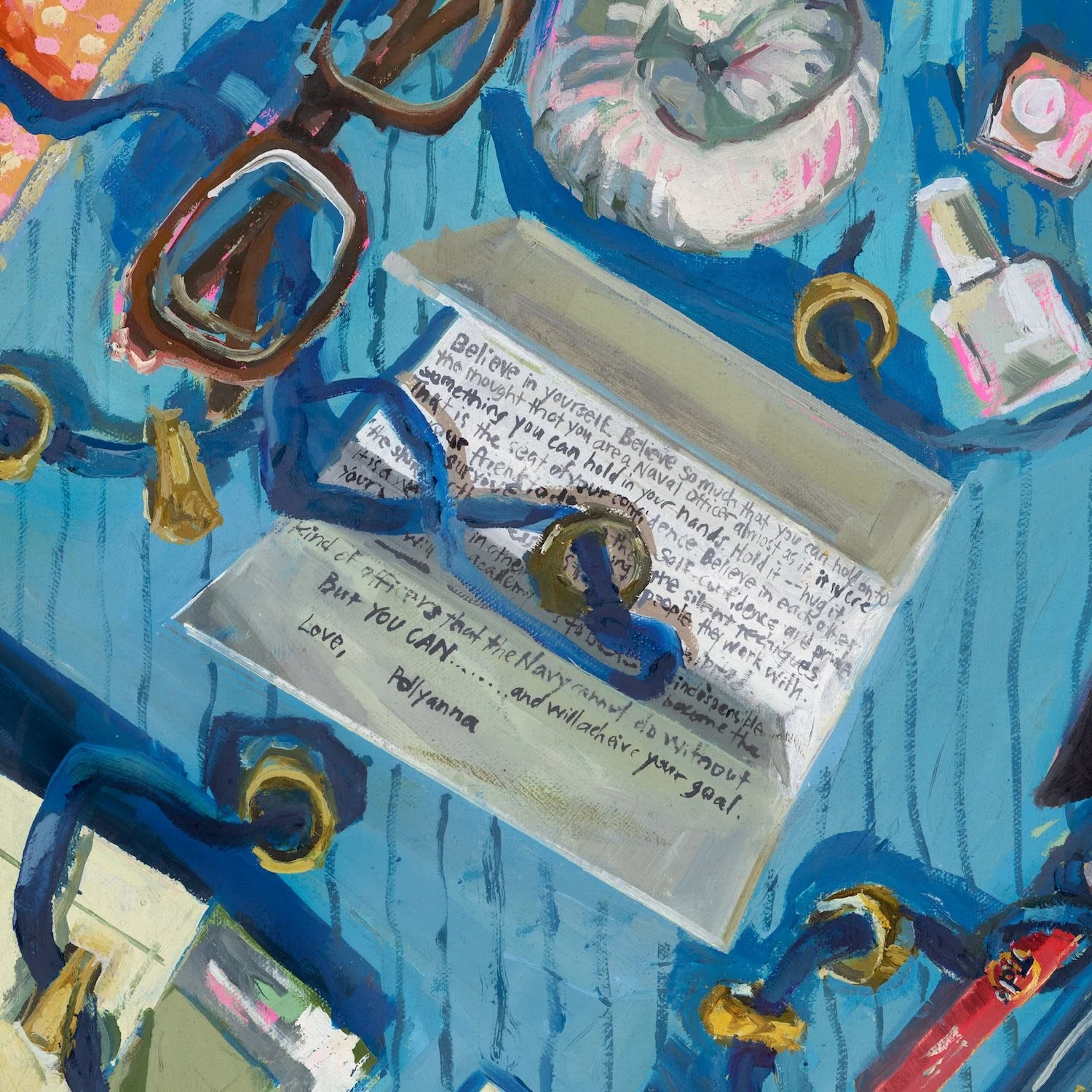

To talk about this, I threaded 50 class rings on a blue ribbon (not unlike what is used during 2/C ring dance,) one for each class.

I also included a letter from Peggy Metzger’s ‘81 mother, Pollyanna, sent in 1979. This letter was typed and mailed to Peg after a shattering moment at a Forrestal Lecture that began with a very brave question from Kathy Bustle ‘82 and a rhetorical response from the Admiral. His reply was immediately misunderstood by all 4000 male midshipmen, who began cheering because they believed his question was an endorsement that women did not belong. I cannot imagine how horrifying it must have felt to be in that room.

Initially an intimate moment of encouragement between mother and daughter, this has become a letter to all of the women, uniting generations. That willingness to share a vulnerable moment is a beautiful example of how we are “stronger together.”

It is my hope the incredible memories these objects ignite are cherished, and the painful ones are reclaimed.